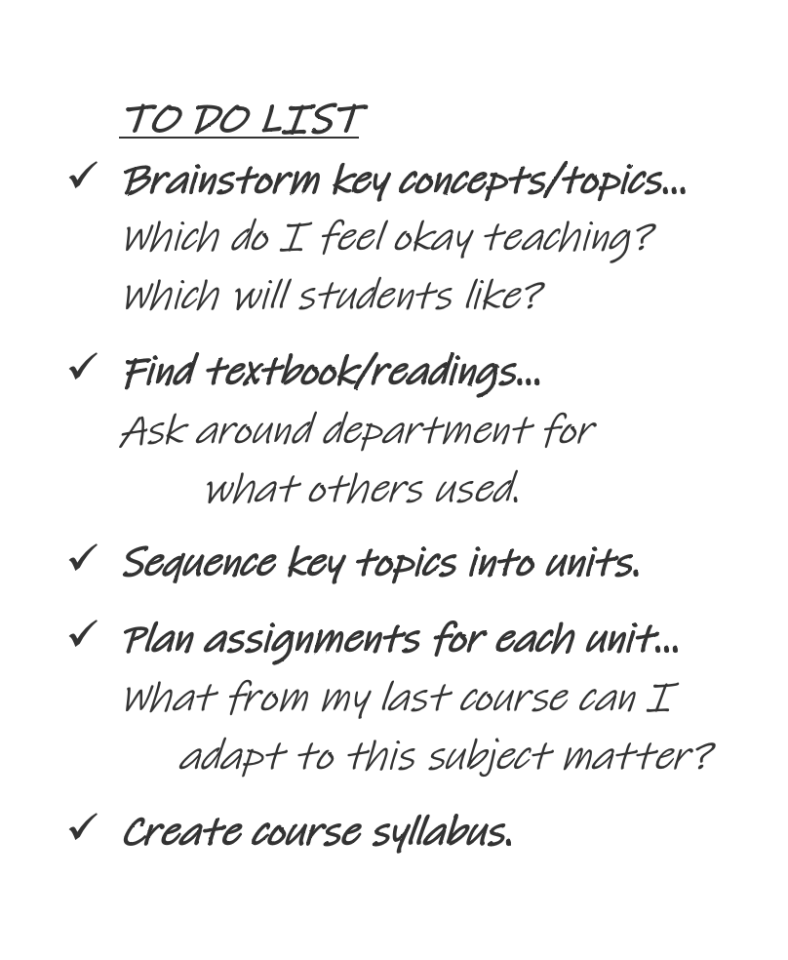

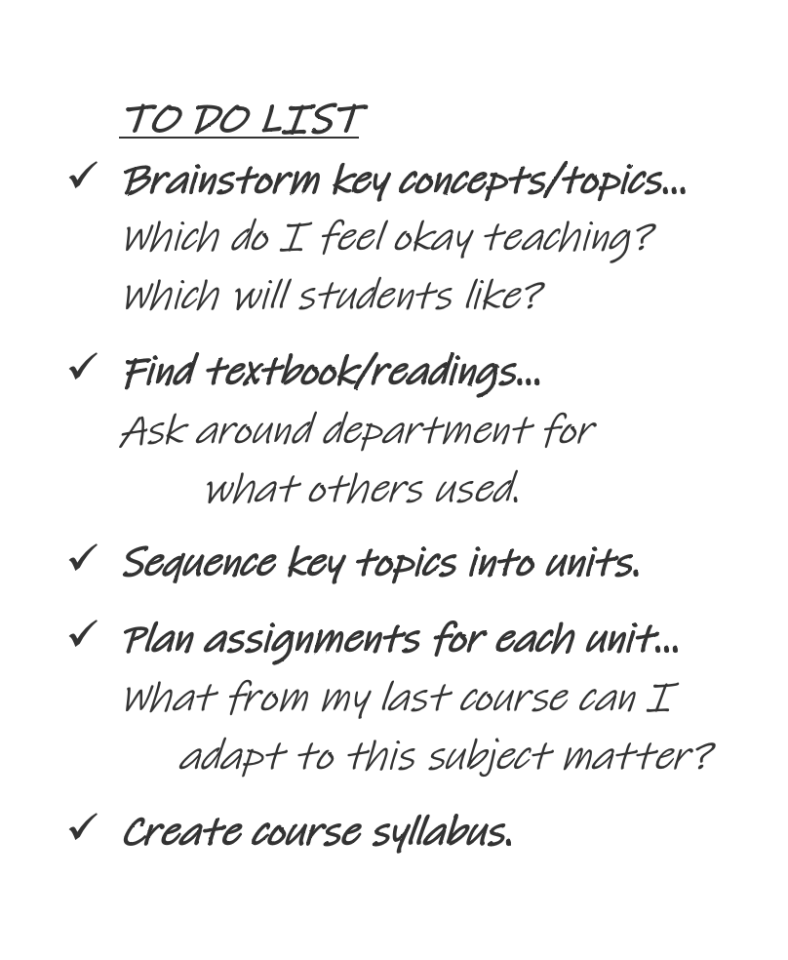

This common approach to course design looks reasonable at first glance, but it also presents some challenges. As experts in their fields, instructors are not always the best judges of what their more novice students might find engaging. And while some disciplinary traditions exist for good reason, others may have developed by chance or worked better for previous generations than today’s learners. Finally, recycling the assignments from a former course may not always be the best fit for a new course. Considering activities that worked well (or not well) in the past is an important part of developing as an educator, but relying too much on previous ideas can lead us to get stuck in our comfort zones, stifling innovation and the opportunity to develop new skills.

We can do better! Whether you're teaching a new course or one you've taught 10 times, adapting an in-person course for the online environment, or even planning a single assignment, it's important to be intentional about your design choices. Backward design is a framework that helps educators plan instruction around what matters most—student learning. This topic will walk you through the backward design process step-by-step, giving you an effective model for planning your next course.

Reflect.

Where do you typically start when you are designing a new course? Have you ever planned a course like Professor Buckeye did? How did it go? Is there anything you would change about that course now?

In a standard content-oriented approach to course design, the design process begins by identifying course content. From there, the instructor plans lectures, activities, and assignments to help students engage with that content. If those lectures, activities, and assignments are effective, students will learn something about the content. Depending on the quantity and quality of learning that results, the instructor might decide to try other teaching strategies the next time they teach the course.

Backward design flips this standard process on its head. Rather than starting with decisions about course content, the backward design process begins by asking you to determine what you want students to learn. Assignments are then developed, with the aim of allowing students to practice and demonstrate that learning. It is only toward the end of the backward design process that decisions about course content finally appear, guided by reflection on what students will need in order to perform well on the assignments. In other words, while traditional course design focuses on planning what and how to teach, with the hope that good teaching will lead to learning, backward design encourages teachers to focus the planning process directly on student learning.

Although backward design has been around for some time (Tyler, 1949), Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe are often credited with its current prevalence. In Understanding By Design (2005), Wiggins and McTighe explain backward design as a three-stage approach to course planning (p. 17-18). The table below lists these three stages, alongside the tasks and considerations that are central to each stage.

| Backward Design Stage | Tasks | Guiding Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Identify desired results. | Create learning goals and outcomes. | What do you hope students will achieve by the end of your course? What should they know, understand, and be able to do? |

| Stage 2: Determine acceptable evidence. | Develop assessments of student learning. | What opportunities will help students practice and achieve the learning outcomes? How will they demonstrate their learning? |

| Stage 3: Plan learning experiences and instruction. | Choose course content and teaching strategies. | What content supports the course learning goals and outcomes? What learning activities will help students engage with that content? What technologies can deliver the content or engage students in the learning experiences? |

Ohio State history

Long before Wiggins and McTighe popularized backward design, Ralph Tyler was working with fellow faculty at The Ohio State University to improve data gathered from assessments. As early as his 1934 article, “Some Findings from Studies in the Field of College Biology,” Tyler details how he helped faculty sketch out the ideas of needs analysis, backward design, and setting behavioral objectives. In Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe reference Tyler as the originator of behavioral objectives (2005, p. 20).

Wiggins and McTighe and other scholars have presented several arguments in favor of a backward design process.

Backward design:

Talking about Learning

Do you ask your students to articulate what, how, and why they are learning in your course? Wiggins and McTighe believe students should be able to answer questions like the following about their course content and activities: "What’s the point? What’s the big idea here? What does this help us understand or be able to do? To what does this relate? Why should we learn this?" (2005, p. 16-17)

This section will break the stages of the backward design process down into the following steps:

As you read—or work—through the guidance for each step below, keep a few things in mind:

Inclusive Course Design

As you backward design your course, you should be planning with all students in mind. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for focusing curriculum and course design around the diverse needs of learners. UDL aims to achieve the highest level of functionality and user-friendliness for as many learners as possible by intentionally designing outcomes, assessments, and materials in ways that promote equal access and positive learning experiences for every student. Backward design and UDL are complementary frameworks for course planning, as each are centered on student learning and purposeful, proactive course design.

When using the Step-by-Step Guide below to plan your course, you'll want to keep your ideas organized. A Course Plan template like the one pictured here helps you outline your course week-by-week, articulate how you will sequence course content, and solidify the timing of learning activities over the semester. Complete the columns of the template in order as you proceed through each step of backward design. Laying out your Course Plan this way will enable you to see the big picture as you work, so you can ensure that all components of your course stay aligned.

Think of your plan as a "course skeleton" rather than as a detailed roadmap. Use as many rows as you need to outline the entire semester. Be prepared to review the columns for alignment, move things around, and update your Course Plan as needed as you progress through each step.

TEACHING STRATEGIES AND LEARNING ACTIVITIES

How will I help students understand and engage with the content? How will students practice and prepare for the assessments?

Your completed Course Plan should lay out, in brief, the weekly assessments, course content, and teaching strategies and activities that align to the learning outcomes you create in Step 2 below.

Click on each step for further details, key considerations, and guiding questions to walk you through backward designing your Course Plan.

Step 1: Formulate the learning goals for students in your course.

When you create your course learning goals , you describe how you want students to change internally as a result of taking your course. L earning goals broadly state what students should know or care about by the end of a course or curriculum. Set aside specific content—remember, that comes toward the end of the backward design process—and think about the big-picture, lasting impact you want your course to have on students.

There is not a set number of recommended goals to write for this step. You’ll probably have somewhere in the range of three to seven learning goals for the course you are designing.

Guiding Questions:

When considering these questions and writing your goals, it can be easy to focus on what you want your students to know or understand about the subject matter. But many of the most exciting and memorable learning experiences go beyond the acquisition of new knowledge. Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning (2013), a framework that details six types of learning that produce these experiences, can help you develop many other kinds of learning goals.

When you’re ready to write your course learning goals, note that they typically begin with imprecise or “fuzzy” verbs that you cannot observe, such as “know,” “understand," "believe," "learn," "appreciate," and "interpret." Write your goals in student-friendly language; after all, students will need to understand the course goals before they can achieve them.

Review these sample course learning goals:

A. Students will understand the impacts of climate change globally and locally.

B. Students will know ways that human activity has contributed to climate change.

C. Students will learn a range of proposed solutions to the climate crisis.

D. Students will appreciate the urgency of the climate crisis.

E. Student will value our environmental resources.

Once you have three to seven course learning goals drafted for your course, consider how you will share them with students. How will you communicate the value of the goals, or demonstrate their relevance to your students’ lives?

Your Course Plan: Add your course learning goals at the top of your Course Plan template to reference as you work through later steps.

Step 2: Articulate learning outcomes to align with your learning goals.To evaluate the success of a course, you must be able to observe the internal changes you identified in Step 1 happening in your students. So in Step 2, you create learning outcomes that describe how those internal changes will manifest externally . Your learning outcomes clarify exactly what it looks like for students to meet your learning goals. Learning outcomes should be specific and stated in concrete, observable, and measurable terms.

Guiding Questions (for each learning goal):

To thoroughly describe what meeting your goals looks like in practice, you will likely develop at least three to four learning outcomes for each goal. If you have a goal that has zero corresponding outcomes, it should not be a learning goal for your course. If you have a goal that has far too many corresponding outcomes, there may be another goal floating among them that you haven't articulated yet. If you have learning goals that are closely related, you may have learning outcomes that correspond to more than one goal in your course.

Learning outcomes often take a form like the following:

Use specific action verbs to express exactly the kinds of skills you want your students to develop. Ensure that various, appropriate levels of challenge are represented in your outcomes so you can measure how close students are to achieving the learning goal.

Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956)—a common framework for thinking about and articulating learning outcomes—can help you identify appropriate skills and action verbs when writing your outcomes. In the revised taxonomy from 2001, the six categories reflect how learners interact with knowledge. Learners can: remember content, understand ideas, apply information to new situations, analyze relationships between ideas, evaluate information to justify perspectives or decisions, and create new ideas or original work.

Consider the sample action verbs for each Bloom's category below:

Read more about Bloom’s Taxonomy and see more Sample Bloom’s Verbs .

TIP: Aligning your goals and outcomes in a table like the one below will help you clearly articulate learning outcomes that support each goal. Review the sample learning outcomes in the table. Do they describe concrete, observable, and measurable actions that can demonstrate whether students are achieving the learning goal?

By the end of this course, students will be able to:

A1: Identify regions of the world most affected by the climate crisis.

A2: Explain why some regions are more affected by climate change than others.

A3: Describe effects of climate change on the environment (e.g., forest fires, droughts, more severe storms, rising temperatures, rising sea levels).

A4: Predict human consequences and health impacts of the climate crisis (e.g., population migration, food access, air quality issues, infrastructure damage, increased disease and mental health concerns).

A5. Reflect upon the impacts of climate change on their local communities and in their everyday lives.

A6: Analyze evidence and data that show climate change is escalating.

Your Course Plan: Draft learning outcomes for each of your course learning goals. Then think about where you will address these learning outcomes over the weeks of the semester. Add them to Column 2 of your Course Plan. A given outcome is likely to appear multiple times across your course (each outcome must be addressed at least once). Remember — you will be able to revisit and adjust your plans as you work through later steps.

Step 3: Design assessments of student learning that align with your learning outcomes.At this point, you have determined what students will know and be able to do by the end of your course. The next step is to create opportunities for students to show that they are achieving those learning goals and outcomes. In other words, Step 3 will center on developing the assessment of learning for your course, including assignments and other graded types of assessment such as quizzes, tests, and projects.

Guiding Questions:

Since you need to track student progress with respect to all course goals and learning outcomes, each outcome should be tested by at least one assessment of student learning. It should be possible to think of several ways to assess a given learning outcome—if you can only think of one way to assess an outcome, then it is probably an assignment.

For your most important learning outcomes, you may need to develop multiple opportunities to measure students' progress over the duration of the course. This will also give students the chance to practice and apply skills in a variety of contexts, incorporate feedback, and get the practice they need to meet upcoming challenges in the course. For these same reasons, your assessment methods will ideally incorporate various degrees of difficulty or skill integration over the semester.

Guiding Questions:

Your Course Plan: Consider when graded assignments, quizzes, exams and so on that align to your learning outcomes will appear in your course. Add them to Column 3 of your Course Plan. Remember — you will be able to revisit and adjust your plans as you work through later steps.

Step 4: Choose the course content students need to succeed on those assessments.So far you have defined your course learning goals and outcomes and planned your assessments of student learning. In Step 4, you will choose the course content that will support students to succeed on those assessments.

Course content includes any textbooks, readings, and media you choose for students to engage with, as well as the content you create yourself — for example, your lecture presentations and any overviews, text, and video you develop for your CarmenCanvas modules. An important part of aligning content to your assignments and assessments is limiting or eliminating material that is redundant or unnecessary. In other words, if it does not align to a learning outcome, you probably do not need to include that content.

Think explicitly about how to organize your content logically given your course subject matter. Possibilities include sequencing it chronologically, around key themes, from simple to complex disciplinary skills, from theory to application, and so on. Also consider any “parallel content” you will include in your course. This is the material you present alongside your main course content to support students with the necessary disciplinary knowledge or foundational skills that underpin or relate to it. You might think of parallel content as the ancillary resources that will help students complete assignments and activities — for example, instructions for research methods, citation guides for works cited, and “how to” articles for using technology tools.

Guiding Questions:

Your Course Plan: Identify course content (and any parallel content) students will need each week to be successful on upcoming assignments and assessments. Add them to Column 4 of your Course Plan. Remember—you will be able to revisit and adjust your plans as you work through later steps.

Step 5: Plan teaching strategies and learning activities that help students practice and prepare for those assessments.

At this point, your Course Plan is well underway. You have selected learning goals, learning outcomes, assignments, and course content. The final step is to select the teaching strategies and class activities that will help students engage with that content, apply their learning on assignments, and meet your outcomes. Do you see how the backward design process helps us keep these course components aligned?

Research shows that retrieving and using information is a critical piece of achieving learning (Karpicke & Roediger, 2008). As such, students must have multiple opportunities to practice and apply the specific knowledge and skills they need to perform well on assignments and be successful in your course. Reflect on your assessments of student learning from Step 3 to determine the teaching methods and learning activities that will best support students to succeed.

Guiding Questions:

Students will also need support to know how to prepare for assignments, to evaluate their work, and to understand their performance. Consider how your teaching strategies and learning activities will explicitly prepare students for assignments and how you can provide tangible feedback on their progress. For example, you might present exemplars and non-exemplars of student work, incorporate checklists for self- and peer review, or simply walk through and discuss the assignment instructions and rubrics you develop explicitly with students.

Guiding Questions:

Your Course Plan: Consider the variety of teaching strategies and learning activities that will help students practice and prepare for your assignments and assessments, and when those activities should occur during the semester. Add them to Column 5 of your Course Plan. Once you complete your plan, check through all columns to ensure the components of your course remain aligned to your learning outcomes and goals. Make adjustments and revisions, as needed.

Choosing technology tools

Most elements of backward design will involve some sort of technology, whether it's a platform in which students are completing or submitting assignments, an ebook or piece of digital media that delivers course content, or a tool that helps students practice applying knowledge and skills during class activities. Be thoughtful about selecting tools that will best support students in meeting your learning goals and outcomes.

Read more in Understanding Learning Technologies at Ohio State and Integrating Technology into Your Course. For a deep dive into choosing and using technology for your course, register for the Technology-Enhanced Teaching course.

Backward designing an online course leads you to be more intentional about your use of the online space, helping to mitigate the challenges of online learning while maximizing its affordances. You will follow the same step-by-step process above, but there are a few additional elements to consider during Steps 3-5.

If you're an Ohio State educator looking for more support with course design, there are a number of resources at your disposal. In addition to browsing our growing repository of teaching topics, we encourage you to explore the following professional development activities.

Seek a teaching consultation.

The Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning offers teaching consultations for individual instructors who have questions or concerns about any aspects of teaching, including the course design or backward design process: Request a consultation with the Drake Institute . If your course design questions are specific to an online context, you may wish to request a consultation with OAA Digital Learning instead.

Participate in a professional learning program.No matter your teaching modality, Ohio State has a professional learning program designed to support you with course design. Successful completion of each option below also earns you a teaching endorsement for Course Design in Higher Education.

Browse additional learning opportunities offered across campus.

Apply for Instructional Redesign.T his Drake Institute program offers guidance and compensation to full-time (.75 FTE) faculty at Ohio State for time spent researching evidence-based teaching practices and redesigning their courses around those teaching practices. Learn more about Instructional Redesign.